The haunting stare of the girl makes me shift uncomfortably. She has big brown eyes. Dishevelled hair thrusts out of her headscarf haphazardly, imparting a chaotic look. In the dark room entranced by the melody of a piano I am alone with her, separated by a barricade. I am new, but she is ancient — more than 2,000 years old. She is the Gypsy Girl, the most prized pictorial mosaic in the Zeugma Mosaic Museum of Gaziantep in Turkey.

In south-eastern Anatolia, Gaziantep is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities of the world, and just 60 kilometres away from Zeugma — an underwater city more than two millennia old.

In 300 BC, Seleucus I Nicator, a general in Alexander the Great’s army, founded two Greek settlements on both the banks of the Euphrates. The city on the west was named Seleucia and the one on the east was named Apamea. The two cities were connected by a pontoon bridge. By the time the Romans arrived in 64 BC, Apamea had already been abandoned due to floods. In a diplomatic move, the Roman king Pompey gifted Seleucia on the Euphrates, to the Commagene king Antiochus I Theos but later, Roman king Augustus reclaimed it back from the Commagene. Under the Roman rule, the city was renamed Zeugma. After a devastating invasion by the Sasanian empire in 256 AD Zeugma’s power was lost forever.

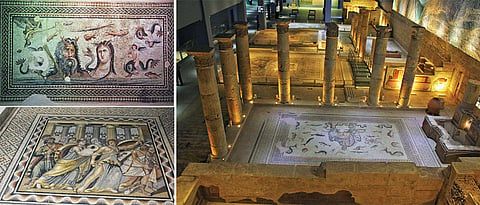

In the year 2000, the construction of the Birecik dam on the Euphrates threatened to flood the ancient city. Official excavations initiated by Gaziantep Museum Directorate started only in 1987, albeit slowly. In the late ’90s when the erection of the dam was approaching, a rushed arrangement was made to relocate and preserve the impressive mosaic fragments. Zeugma Mosaic Museum was opened in 2011 as a repository of the artistic wealth of the lost city of Zeugma.

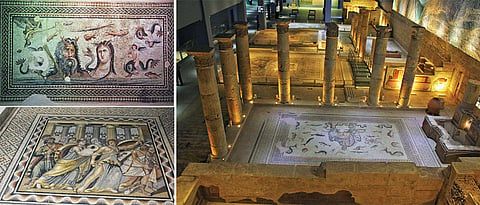

Greek god Oceanus, who rules all the seas of the world except the Mediterranean Sea, and Tethys, who symbolises the female element underwater, are the main subjects of the first wall mosaic I set my eyes upon as I enter the museum. A sprawling floor mosaic of Akratos, god of pure wine, filling the glass of his wife Euphrosyne from a deer-headed drinking pot, bordered by geometric patterns, catches my eye next. The mosaics exhibited here are set in chronological order. Spread over an area of approximately 2,500 square metres, Zeugma Museum is the largest mosaic museum in the world in terms of floor area.

Due to its strategic position on the silk route, Zeugma attained a place of importance in the Roman Empire. From retired officials to artists, everyone settled in Zeugma and enriched it. The hill city was divided into five zones — the northern part was for administration and legion, the eastern and north-eastern side were neighbourhoods and the southern and western part comprised the cemetery. Above the acropolis of the city was a temple of the goddess of fortune and fate — Tyche. Nobles in the Roman period were expected to live on higher grounds, a practice which explains the existence of the exquisite villas with detailed mosaic floors and walls on the upper terraces of the slope.

Though the original city is now sleeping under the waters of Euphrates, Zeugma Mosaic Museum is an attempt by the authorities to recreate an impression of the submerged city. The crumbled walls and dilapidated columns which enclose the floor mosaics give the visitor a sense of the classical metropolis. The occasional swells in the walkway, which represent the bridges of the city, also provide good vantage points to appreciate the floor mosaic work.

I am walking on such a bridge when the mosaic of Metiochus and Parthenope sitting on a sofa vies for my attention. Parthenope, the sister of the king of Samos, had taken an oath of virginity for the sanctity of her family. But she fell in love with Metiochus, a love which would never reach fruition. The upper part of the mosaic was missing when it was excavated in 1993. Antiquity smugglers had discovered the wealth of mosaics at Zeugma long before it got government attention. Throughout the ’90s, the mosaics of Zeugma were plundered and sent to Syria on camel back. The missing part found its way to an American University in Houston which was later brought back to Turkey through diplomatic channels.

The floors and the walls are decked with tales from the Hellenistic pantheon: the kidnap of Persophone, the discovery of Achilles among the daughters of Lycomedes, Europa’s union with Zeus, Pasiphae and the birth of Minotaur and many more. However, the Gypsy Girl mosaic found in the Maenad Villa has overtime become the icon of Gaziantep. The girl is often interpreted as the Greek goddess of Earth, Gaia, some draw similarity with Leonardo da Vinci’s Monalisa, whereas others point out its striking resemblance with Steve Mc Curry’s photo ‘The Afghan Girl’.